“There is an over-reliance on the criminal justice system and the police to address health and social issues including the enforcement of COVID-19 regulations.”

Accountability International began the Challenging Criminalisation Globally Project as a way to catalyse multi-movement and inter-movement involvement in rethinking and re-strategizing around how a larger variety of stakeholders can challenge criminalisation collectively, with a particular focus on communities and civil society from low- and middle-income countries. This is in response to a global clampdown on people who are perceived to be “criminal” because of issues such as houselessness, suicide and euthanasia, migration status, and road crashes.

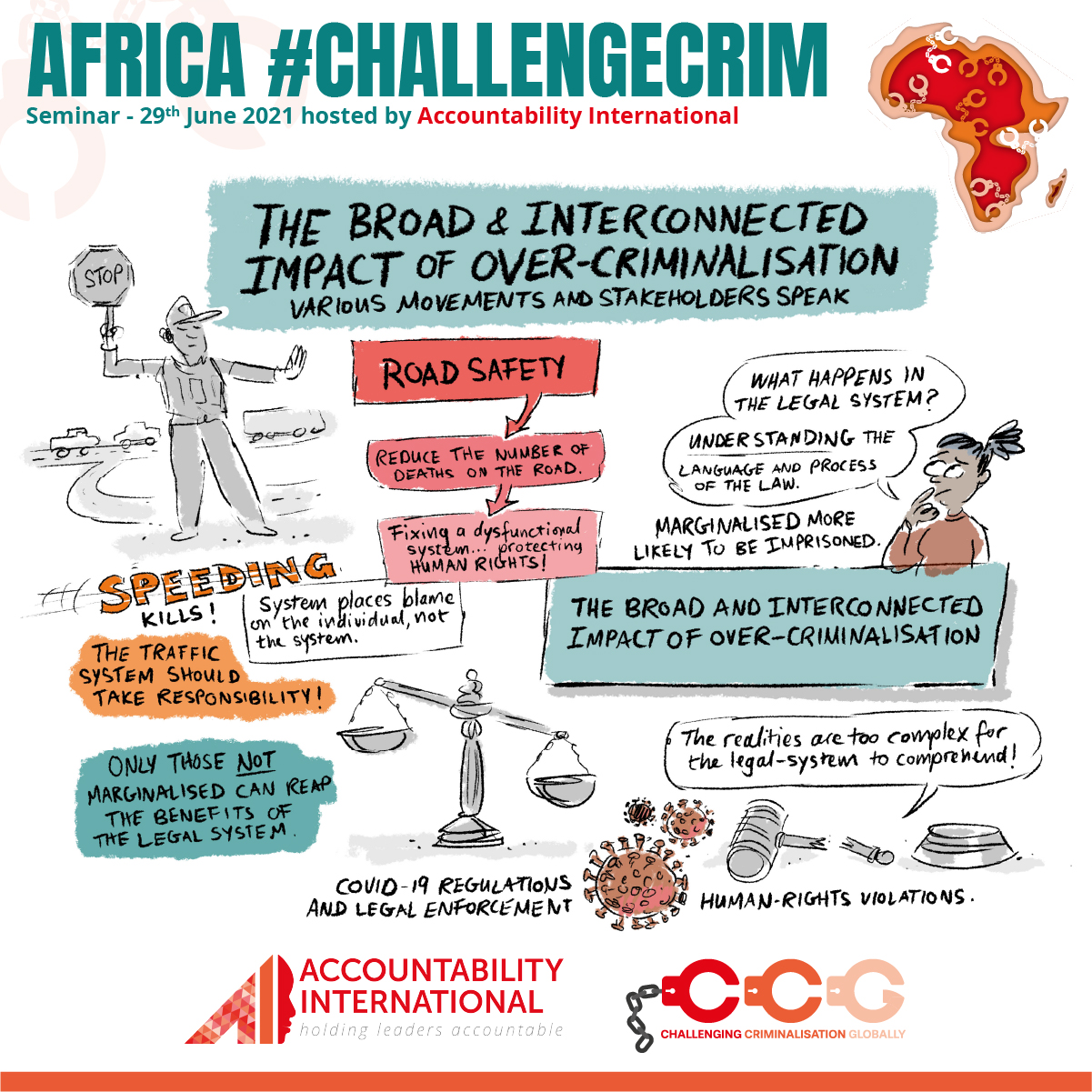

In July 2021, Accountability International brought together academics, activists, and NGOs from different fields in a one-day seminar, Africa Challenges Criminalisation. The conference brought together advocates from fields as diverse as sexuality, suicide, and COVID-19 to explore a common issue: how over-criminalizing behavior is hampering progress on the SDGs. The interconnectivity of the theme is demonstrated in graphics created by the seminar’s artist during the panel.

Lotte Brondum, speaking during a panel on the broad and interconnected impact of criminalization, alongside representatives from Amnesty International, Fair Trials, and The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria, pointed to the Safe System approach as a way of addressing the traditional view of road safety where blame for crashes is often placed largely on road users without considering the failings of the system.

The Safe System views human life at the center of the mobility system. It accepts that human error is inevitable and, instead of criminalizing road users for errors that are bound to happen, looks at how all aspects of the road system must work to minimize the impact of those errors to achieve zero deaths (Vision Zero). In the Safe System approach, as well as tackling road user behavior, vehicles must have safety features to support drivers, the road infrastructure must be forgiving, road and transport policy must put people at the center, and post-crash care must be easily available in case of a crash.

This differs from the still prevalent idea that instructing road users to drive at an appropriate speed (even if those limits are inappropriate), not use their phones or drink alcohol, and wear seat belts, is the primary focus on road safety. This leads to criminalization of road user behavior at the expense of other factors. It reduces accountability on governments to protect their citizens. Taking this narrow, behavior-focused view of road safety ultimately reduces potential to achieve SDG 3.6, to reduce road deaths and injuries by 50% by 2030, as well as other linked SDGs including gender equality, education, poverty and more.

During the seminar, several speakers reiterated that the legal system does not treat everyone equally and that one of the limitations of criminalization is that it punishes some more than others. For example, people from a lower income class and who are otherwise marginalized, by race, migration status, gender, etc. are more likely to be prosecuted and receive harsher sentences. Another key point raised was that criminalization does not actually have the preventative and protective effect that many believe it does; education has much greater benefits in changing behavior, and structural, social-economic adjustments play an even greater role when it comes to issues of criminalization.

Setting road safety in the context of other rights such as gender, sexuality, poverty, and justice, and other approaches to tackling issues is a theme that the Stockholm Declaration and the recent UN Global Road Safety Week campaign have both highlighted. We will achieve our goals more effectively when we link our agendas.

Read MORE.